Aside from Port Jackson and Botany Bay where the French expedition of Jean-François de Galaup, perhaps better known as the Comte de Lapérouse (Count of La Perouse), met with the First Fleet in 1788, just three days after the British had arrived, this area of Australian coastline is named after An encounter by two famed 19th century French and British explorers – hence the name, Encounter Bay. Despite the fact that Britain and France were at war at the time, the two navigators exchanged cordiality and information of their charting of the southern Australian coastline.

This southern Australian coastal region is the site of one of South Australia’s most picturesque coastal cities – Victor Harbour. Despite its link with early Australian history, his thriving coastal metropolis is now more renowned for surfing, whale watching, a famous tramway and triathlons.

In October 1800, French navigator Nicolas Baudin commanded an expedition to the south seas to complete the French survey of the Australian coastline, and make scientific observations. His expeditionary force consisted of two ships, Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste. The French ships arrived near Cape Leeuwin off the Western Australian coast in May 1801. Following their instructions, both ships sailed north along the western coast of the continent. After staying at Timor, the French then sailed south to survey Tasmania or Van Diemen’s Land, as it was then known. In following this itinerary, they missed the opportunity to be the first Europeans to survey the then-unknown southern coast.

By early April 1802 Baudin, aboard Le Geographe was in South Australian waters. He sailed westwards along the southern coastline, meeting Matthew Flinders aboard the British sloop HMS Investigator at a picturesque bay on the southern Australian coast, dominated by a large granite island. The bay was named by Flinders as Encounter Bay, in honour of his meeting with Baudin. Shortly after their encounter, Baudin headed his ship north towards the New South Wales coast where the British settlement was now firmly established at Sydney Cove.

After spending the winter months at Port Jackson, Baudin returned to the southern Australian coast for a more detailed survey, and in January 1803 circumnavigated Kangaroo Island, although Flinders had been there before him. By the end of February Baudin’s Le Geographe had rendezvoused with another French ship, Casuarina after Le Naturaliste had returned to France. The two ships then explored the west and northwest coasts of New Holland, as Australia was then known, before heading home via Timor.

Baudin died in 1803 on the homeward voyage, so publication of the account and charts of his voyage was undertaken by Francois Peron, the expedition’s naturalist. The first volume of Voyage de decouvertes aux Terres Australes and Volume I of Atlas, which included plates, was released in 1807. French place names were recorded for ‘Terre Napoleon’ west of Wilson’s Promontory. As Peron died in 1810, cartographer Louis de Freycinet continued to edit the voyage’s account, and in 1811 he published the second part of Atlas, which featured the charts of the expedition, again recording French place names on ‘Terre Napoleon.’

The French expedition’s charts were published in 1811 – three years before Flinders’. Freycinet’s Carte General de la Nouvelle Hollande was therefore the first chart of Australia, bringing together the results of English and French surveys. The French charts are generally acknowledged as beautiful with their elaborate title cartouches with flora and fauna. However, Flinders’ charts are notably superior, in particular those of the now revealed ‘unknown coast’. Flinders was meticulous for the precise surveying he carried out, both onboard the Investigator and ashore. Matthew Flinders and his brother Samuel, who was responsible for the astronomical observations that were so necessary a part of the survey, were extremely competent surveyors, far more so than those on the French expedition.

In the end however, claims of ‘primacy’ – or who was where first – were what mattered most to the authorities and to Flinders. With the French charts published first, with French names along the length of the South Australian coast, they laid a claim to that portion of the continent and called it Terre Napoleon. When Flinders’ charts were finally published in July 1814, he was scrupulous in honouring prior discoveries on the coast – hence ‘Discovered by Nuyts 1627’ and ‘Discovered by Captain Baudin 1802’, which marked the western and eastern limits of his discoveries.

It was not until the second edition of Voyage de decouvertes aux Terres Australes was published in 1824 that French place names were only recorded where the French had been the first to survey along the southern coast, mainly in the south-east and on the southern coast of Kangaroo Island, and Flinders’ discoveries and place names were restored by the French authorities, so Encounter Bay remained the place where the two noted explorers had met.

Flinders had been suitably impressed with the area around Encounter Bay, which is just a few kilometres from the mouth of the Murray River. While the area was sparsely populated from the time of Flinder’s visit in 1802, by whalers, sealers and fishermen, the area wasn’t settled for another 37 years.

History tells us that in 1837, a Captain Richard Crozier anchored in the lee of Granite Island and gave the adjacent part of the mainland the name of his ship HMSVictor.

A Congregational clergyman, Ridgway William Newland, from the south of England, led the first true party of settlers to Encounter Bay in July 1839. The group comprised his family, some relations and friends along with several skilled farm workers and their families.

Newland had obtained letters of introduction to Governor George Gawler from Lord Glenelg, Secretary of State for the Colonies. Gawler told Newland that the village of Adelaide was becoming overcrowded, that most of the nearby land had been taken up and excellent land was available at Encounter Bay for the princely sum of one pound an acre.

Newland took his advice and settled at Encounter Bay. Whaling and farming became the primary enterprises at Encounter Bay. Whaling stations continued trading until around the mid-1860s, but much larger profits were to be had from boats carrying wheat and wool down the Murray River to the port of Goolwa. Since Goolwa was unsuitable for ships, a 12 kilometre railway was built to connect with Port Elliot in 1854 – creating Australia’s first public railway. But Port Elliot was also found wanting as an anchorage for merchant shipping so a safer, more sheltered port in the lee of Granite Island, in Encounter Bay, was chosen. The railway was extended from Port Elliot to Victor Harbor in 1864.

By the early 1870s, Victor Harbor had become a popular seaside holiday destination for Adelaide’s well-to-do and landed gentry. Victor Harbor began to develop as a tourist resort during the 1890s. The closeness to Adelaide, the prominent Granite Island, the causeway with visiting ships, and the cool summer breezes were popular attractions.

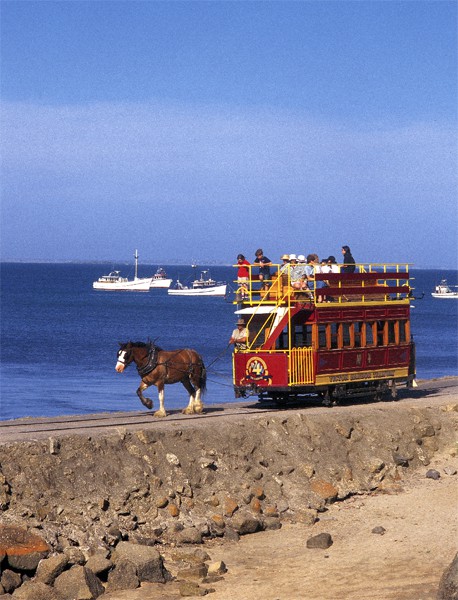

The horse-drawn railway was extended along the Causeway to Granite Island in the mid-1860s to service large American and European clippers plying the wheat and wool trade from South Australia’s lush farmlands to the north and along the Murray River. By the 1880s, 25,000 bales of wool from western New South Wales and Queensland were being paddled down the Murray, freighted by train to Victor Harbor and then shipped to the world. However, the more efficient railways killed the Murray River trade in the 1890s and Victor Harbor’s history as a holiday destination began. Granite Island’s improvements began in 1888 when the council began planting trees on it. The horse tram passenger service to the Island ran from 1894 to 1954. The service was re-introduced in 1986 and is still a favourite with holiday makers, although it is now closed until June 2012 for restoration and reconstruction works. In 1910 the Railways Department took control of the Island and cleaned it up. They constructed a pathway around the island, planted additional trees, erected seats and swings and a ramp to the top of the cliff at the island’s eastern end. The island is the home of Fairy Penguins which are also popular with visitors to the island.

By 1927, the population of Victor Harbor had swelled to 2500 people however annual visitors to the popular seaside town numbered in excess of 60,000 annually.

So popular was the township and surrounding area, just 80 kilometres from Adelaide, that on 26 December 1936 the Australian Grand Prix was held at Victor Harbor. (Thus the Grand Prix of the 1990’s in Adelaide was not the first held in South Australia).

The popularity of Victor Harbor and Encounter Bay as holiday areas helped to cushion the town from the worst effects of the Great Depression in the 1930s and the war years.

In 1969, Granite Island was declared a fauna sanctuary and in 1996, the Café and Penguin Centre opened on the island.

By 1991, more than 125,000 people visited the area to see the South Right whales who pass the bay on the annual migration. The number is growing annually.

Today, Victor Harbor is popular for so many reasons, not the least being the Granite Island Horsedrawn Tram, the Urimbirra Wildlife Park, the Encounter Coast Discovery Centre, the South Australian Whale Centre, the Granite Island Nature Park, fishing and surfing. Victor Harbour also hosts an annual schoolies week in late November. But be warned, while Victor Harbour is noted for its surf, it has a large population of sharks and several recent deaths from shark attacks have been reported.

During major holiday periods, the population of Victor Harbor increases many-fold as there is a good range of quality accommodation available from beachfront apartments to caravan parks. The waterfront precinct comes alive with attractions creating almost a carnival atmosphere.

However there is no escaping the historical significance of Victor Harbour and Encounter Bay to Australia’s early settlement. During 2002, Victor Harbor celebrated the 200th anniversary of Captain Matthew Flinders meeting with Captain Nicholas Baudin at Encounter Bay. The Encounter 2002 Flag Pole sculptures found on the Esplanade opposite Warland Reserve mark this significant occasion. The three impressive flagpoles stand some 15 metres high, the flag poles represent ‘Three Worlds’ and ‘Three Cultures’. The vibrant poles recognise the association between the British, French and Aboriginal cultures entwined through wind and water. At the Visitor’s Information Centre there is also a bronze sculpture of Trim, Matthew Flinders’ famous cat who was aboard Investigator when Flinders met Baudin in 1802.

But why is Victor Harbour spelt without a ‘u’ in harbour? It appears that the spelling of Victor Harbor without the ‘u’ started in the early days of the Colony. It was around the turn of the century that the ‘u’ crept into the spelling of Harbor with new businesses spelling it including the ‘u’ (which is the way most people would have been taught to spell harbour, as the population was largely of British stock. The Victor Harbour Railway Station is still signposted today with the spelling including the ‘u’. Victor Harbor was declared a legal Port on 28 June 1838, a little over a year after Newland had settled in the area. The settlement was officially known to the Harbour’s Board of South Australia as Port Victor until 1921. In 1921 due to the similarity of the name to Port Victoria on South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula and the confusion it caused, it was decided by the Harbour’s Board to change the name back by proclamation to it’s original name of Victor Harbor.

The local newspaper the ‘Victor Harbor Times’ has always been printed without the ‘u’ since it first published in 1912. The township was officially gazetted in 1914 as the ‘Municipal Town of Victor Harbor’. Poor spelling by the Surveyor-General of South Australia, at the time, is credited as the reason why Victor Harbor is spelt without the usual ‘u’ in harbour.

Victor Harbor, with its tall Norfolk Pines dominating the shoreline and the imposing Granite Island surrounded by the clear blue waters of Encounter Bay is amongst the most picturesque spots on Australia’s southern coastline. Its buildings too, have a definite architectural style and many impress and are beautifully maintained. Combined with its historical significance, it is a compelling destination.

Story & Photography: Peter Scott

Peter is a real adventurer who loves jetting off to new places. He's a big fan of exploring different countries and getting to know their cultures. He's also a huge food lover. Wherever he goes, he can't wait to try out the local grub and discover all sorts of tasty dishes.

Peter is a super friendly guy who can't resist a good chat. He loves meeting new people and always finds it cool to learn about their backgrounds and cultures. He's always ready for a chat, whether it's about their life stories or their local traditions.

Because he's travelled so much and tried so many kinds of food, Peter knows a lot about different places and their cuisines. His stories and insights, filled with his own unique experiences, are always interesting and fun to hear. This makes him a great person to hang out with, whether you're having a conversation about world cultures or just looking for some travel tips.

Oh this is wonderful. I visited Victor Harbor 2 weeks ago on the long weekend and saw the new bridge they have built to Granite Island. The horses are just lovely and I got to pat Isabella, what amazing horses they have.